Violinist Mark Wood was a founding member of Trans-Siberian Orchestra, a platinum-record rock group that blends heavy metal music with orchestral sounds. Mark has his own band now and is on a mission to revitalize the symphony orchestra in popular culture. He headlines with the Gulf Coast Symphony on November 21 at the Barbara B. Mann Performing Arts Hall.

Here is Mark’s story:

Mark Wood was born into a creative family in the commuter town of Port Washington, N.Y., on the northern shore of Long Island. “I was probably the luckiest person in the world. My father is a famous artist and my mother was a concert pianist.”

Mark’s mother Jackie shepherded her four boys into string instruments to make an all-brother string quartet, with Mark on viola. “All my brothers now are professional string musicians in orchestras.”

Mark initially wanted to play the tuba. “My mother said: ‘No, you’re going to play viola.’ Well, I didn’t even know what a viola was, but Mom’s always right. So, I said ‘yeah, sure, that sounds great.’ In hindsight, if I played the tuba, there is no way I would have a career anything like what I have now.”

In those formative years, Mark was captivated by a wide spectrum of music. “Not only did I explore Brahms and Mozart and the magnificent repertoire of classical music that I still listen to every day, but at that time there was a band called the Beatles.There was led Zeppelin. There was Jimi Hendrix. There was Woodstock. All brilliant music.”

Still, despite his eclectic musical tastes, Mark was purely a violist through his schoolboy years. When he was 15, his talent took him to a summer music program at the Boston Symphony’s Tanglewood Music Center, where he was mentored by Leonard Bernstein for eight weeks.

That was a life-changing experience. “After I worked with Leonard Bernstein, I got into Juilliard — at 16 years old. I really didn’t realize how good a violist I was. Juilliard was incredible. Nigel Kennedy (violinist) was one of my roommates. He was 14 years old. My other roommate was (violinist) Schlomo Mintz.”

So Mark left high school early and went straight to Juilliard. There, he worked with some of the most-prominent teachers of the era. “Even before Juilliard, my mother had made sure I and my brothers were studying with the best. At 13, I studied with a sectional violist of the New York Philharmonic — Eugene Becker. “I just adored him. He fixed my technique, and we would go deep into really complex works like those of Paul Hindemith and Béla Bartok.”

Just Gimme that Rock n’ Roll

While delving into his Classical music studies, the adolescent Mark was seduced by the sirens of the New York music scene — rock, punk and jazz. “This was New York City in the 1970s, which meant (legendary music club) CBGB, Miles Davis, the punk movement and rock.” Even the Classical music universe was expanding, moving away from pure tonality, with composers such as Edgard Varèse and Krzysztof Penderecki. “I loved them all.”

Mark’s viola teacher at Juilliard was William Lincer, a traditionalist Classical teacher who was training him eventually to become principal viola in a top orchestra, such as the New York Philharmonic, where Lincer had once held that chair. Mark also studied with renowned violists Walter Trampler and Paul Doktor.

That experience was inspirational for Mark. Well, except for the comportment expected of Classical musicians and Juilliard students. “You couldn’t wear sneakers with your tuxedo. You couldn’t play other styles of music. You had to be pure-bred on the viola. They didn’t want us hanging around with musicians from other genres. When I went in and asked Lincer if he’d teach me how to play like Van Halen on my viola, he almost threw me out the window.’”

Mark says that while he was at Juilliard, a recording came out that changed his life. That was rock legend Eddie Van Halen’s first record. “I would listen to his virtuosity and think: ‘Man, I could do that on my viola.’ He was doing something in his solos that was much closer to what we were doing in Classical music.”

Well, the writing was now on the wall. After two years at Juilliard, Mark left to explore who he was meant to be as an artist. “My heroes were not just the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Brahms and Beethoven, Mozart, Starvinski or Bartok. They were also Led Zeppelin, the Beatles and others in rock, as well as those in fusion, such as Weather Report and Chick Correa, and Miles Davis in Jazz.”

With that, a 17 year-old Mark Wood, refined by Juilliard and the finest of viola teachers, went back to Port Washington and handed his musical higher education over to local self-taught rockers who couldn’t read or write music. Though they could sure play.

“I was hanging out with all these great Long-Island musicians in the 1970s. I would walk in with these charts and they would say: ‘Get rid of that sheet music. We’re gonna learn by ear. Back then and to this day, the bulk of rock music in the world is taught and learned by ear.”

At the time, Long Island had a music scene in which rock clubs dotted the landscape, Mark says. “I was able to play in bands constantly. It was all glam rock, David Bowie stuff and music influenced by British rock. Billy Joel was up and coming. There was a big list of great bands, like Twisted Sister. And I was friends with them all. I was this weird outcast who played virtuoso rock on string instruments I had built myself.”

Going Where No Rocker Had Gone Before

Enter the violin. Mark says viola wasn’t going to work as a rock instrument. His friends suggested he play the guitar. And while Mark adored the guitar, it wasn’t for him. He wanted to stand out purely as a rock violinist. And those were scarce. “If you were playing a bowed instrument at the time, you were doing country fiddle music, Classical music or some jazz. That was it.”

It was Led Zeppelin that helped clarify things for Mark. “When I heard Kashmir, it blew my mind. It was mixing Middle Eastern music with rock, with guitar and big drums. That was exciting. It was a revolutionary approach of which I needed to be part. But on my terms.”

To achieve that dream, Mark devoured the creative and improvisational rock music on Long Island. “I was learning about that scene as a student. I was a trained classical viola player. Then all of a sudden, I’m around self-trained musicians who say: ‘Mark, play something for us.’ I ask, ‘play what?’ And they say, ‘well, anything, just jam.’”

Well, that was easy for them to say. At that moment, Mark couldn’t play one note on his own because he wasn’t taught to improvise. “Classical musicians are really attached to those black dots. And my rock heroes did not deal with that all. They dealt with the ear.”

Mark does concede that great Classical musicians are something more than notation parrots. “Okay, they are doing something on a much higher plane. But as a Juilliard student, I was taught to come in, not look at anything but the viola part, play it and then go home. You had to blend in musically and visually into this wonderful musical structure that has been around for 400 years.”

Fair enough. But Mark wondered if he could countenance such boundaries for an entire lifetime. “That’s why I jumped. It was a clean break, and I never returned. My Juilliard teachers ostracized me.” Ironically, Mark now mentors at Julliard. He says that five years ago, the school reached out and asked him back in an expert’s role.

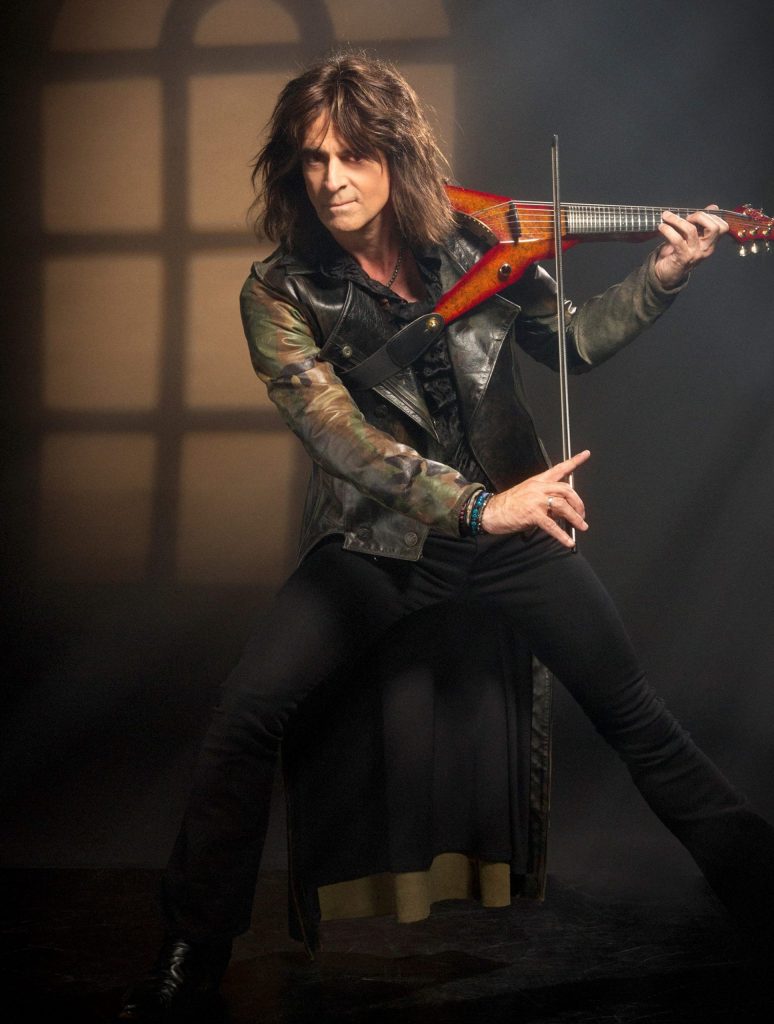

Mark is pictured at left with examples of electric violins manufactured by his company Wood Violins.

Since he was 12 years old, Mark had experimented with making solid-wood electrified violins. Such instruments were nonexistent at the time, he says. His first creation was a pink, dragon-winged number that he would strap to his upper body to give him more freedom of movement. And Mark has continued crafting electric violins to this day.

He says making electric violins went hand in hand with his musical awakening and family background. The inclination toward woodworking came from his grandfather, Albert Wood, who he says was Henry Ford’s architect, designing factories for the Ford Motor Co.

Later in life, Albert moved the family from Detroit to Port Washington and manufactured wooden furniture for houses of worship. Mark says that in his younger days, he sourced exotic woods for his violins late at night from his granddad’s shop, which was next door to his father Paul’s art studio.

‘Son, Can You Play Me a Melody?’

For seven years after leaving Julliard, Mark squatted in his father’s art studio as a struggling rock musician who played $50-dollar-a-night gigs around Long Island and built electric violins on the side.

Yet, his dad offered Mark more than just a place to crash. He also contributed to his son’s musical transformation. “I’d watch my father create art instantaneously as a painter. His creative fluidness was what I had been missing in my pedagogical experiences in the past.”

Mark got his big break when, on a whim, he sent a demonstration cassette to Guitar Magazine, which subsequently published a story about him. There were few, if any, heavy-metal solo violin acts around in those days. And suddenly, Mark got noticed. A year later he won a record deal. “I got a publicist. I was on the Tonight Show and in Time Magazine. My career just exploded. I was hanging out doing concerts with Randy Rhoads, Ozzie, Van Halen, Pantera, Zappa and a bunch of others.”

But then the band Nirvana arrived on the scene with it’s “gunge rock” sound that was a hybrid of punk and rock. With that, the rock scene changed direction, leaving behind a refined style that revolved around virtuosic solos, Mark says. “The music industry was MTV driven, and once Nirvana hit no one wanted to hear virtuoso soloists.”

All wasn’t lost, however. For the next couple years, Mark was able to live off his film-scoring income. He had bumped into a filmmaker for whom he ended up writing a score. And that line of work began to flourish as he got other jobs. This was when he was in his early 30s. He wrote music for the 1992 Olympics and other sporting events, eventually winning an Emmy Award for the theme of the 2002 Tour de France.

“Sports music at the time was moving away from the clichéd soft theme to hard-hitting anthems. And I could do that. So, I ended up writing the theme for a Super Bowl; I wrote themes for U.S. Open tennis, for golf tournaments like the Masters and for NASCAR. I wrote a tremendous amount of music.” Mark still composes music.

“We didn’t think anyone was going to buy this kind of music.”

Around 1994, Mark says, he was approached by guitarist Al Pitrelli, who was one of a group of musicians forming a rock ensemble that would blend orchestral music with heavy-metal rock. Pitrelli was a guitarist of some repute, having played with Megadeth and Alice Cooper. “I went to high school with him. This was my buddy from Long Island. We were all these greasy New Yorkers putting together this ‘electric orchestra.’”

The group put together a demo tape of a heavy-metal version of the Carol of the Bells. Mark says. “We didn’t think anyone was going to buy this kind of music. Still, we threw it out to a radio station. They played it around Christmas time, and it exploded in popularity on the radio. So we formally formed the band and made a record.” And thus, Trans-Siberian Orchestra was born.

Mark became the original lead violinist and a founding member of TSO. But the band’s first public appearance wasn’t in some venerated hall or club. “No, our first gig was on the QVC shopping channel to pitch the Christmas record. That performance and our record went over big.” Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s portfolio of works has since sold more than 10 million recordings.

TSO tours were year-end holiday oriented. For the rest of the year, Mark would record some, and he’d prepare for the next tour. After a while, though, it became a grind. Mark was with Trans-Siberian Orchestra for nearly 15 years. “By then, playing in the band was becoming really all-consuming and cumbersome for my life.” So he left the band in 2009.

And He Dreamed of Another World

Just before his departure from TSO, a local music teacher approached Mark after a concert at the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and asked him if he could put together a Trans-Siberian-type orchestra for his high school. “After Juilliard, I didn’t want to go near a classroom. But the idea intrigued me.” So Mark went around to the school to have a look, and the rest is history.

Mark has since formed an educational outreach company called “Electrify Your Symphony.” It has now been going for 25 years, operating nationally and internationally. It helps school choirs, bands and orchestras integrate a more diverse approach to music, including improvisation, but built on a Classical-music tradition.

Mark’s and his school-mentoring team are on the road eight months of the year. That is, until the COVID pandemic hit in March. And now, the program is going online. “My vision continues to be bringing the symphony orchestra back to the popular mainstream. Four hundred years ago, the orchestra was the hub of activity. But now it’s not.The symphony orchestra needs a rejuvenation. That means educating the kids about it.”

Mark has his own band, in which his child Elijah Wood plays drums. Elijah is also the drummer for singer Shania Twain. And Mark’s wife Laura Kaye is a professional singer in her own right. Mark’s concert on November 21 with the Gulf Coast Symphony will be his first stage appearance since March.

Meanwhile, Mark says his violin-making is going strong. He has five full-time and two part-time luthiers building the instruments by hand in his Long-Island workshop, which has a year-long waiting list for his electric violins. “The orders keep coming in, despite the pandemic.”

Still, Mark’s musical mission isn’t complete. He’s keen to bring in a new generation to the concert halls and to witness the power of the great symphony orchestras. With his music-education outreach EYS, his summer music festival/camp MWROC, his manufacturing company Wood Violins and his performing, Mark has the vehicles to drive his mission to bring people and diverse forms of music together to celebrate creativity.

And that ain’t fiddlin’ Dixie.

By Art Mooradian

For more information about Mark Wood and his music, check out his website at www.markwoodmusic.com. To learn more about Mark’s electric violins, visit www.woodviolins.com. And read about his musical educational outreach Electrify Your Symphony at www.electrifyyoursymphony.com